...using documents, images, maps and online tools

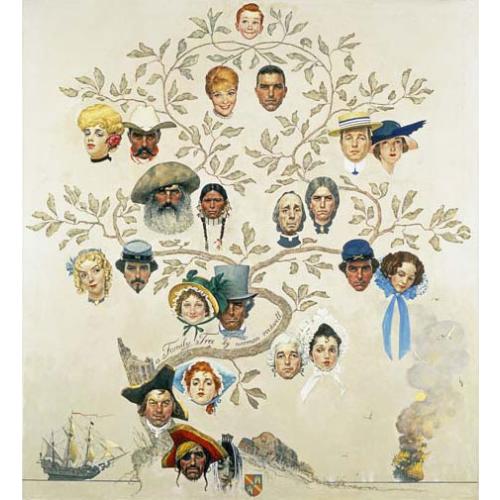

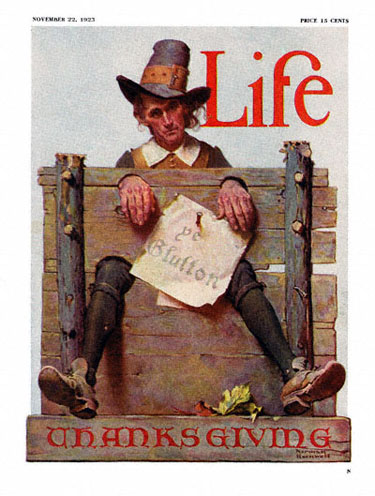

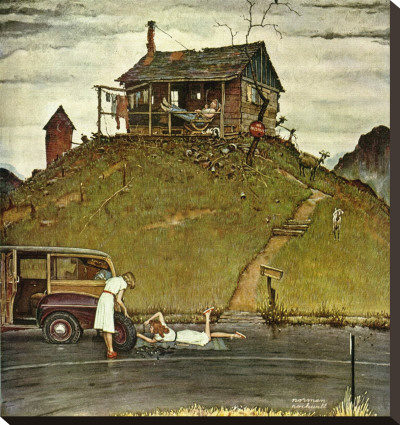

Norman Rockwell's Family Tree 1959

Norman Rockwell's Family Tree 1959 Tags:

Views: 4147

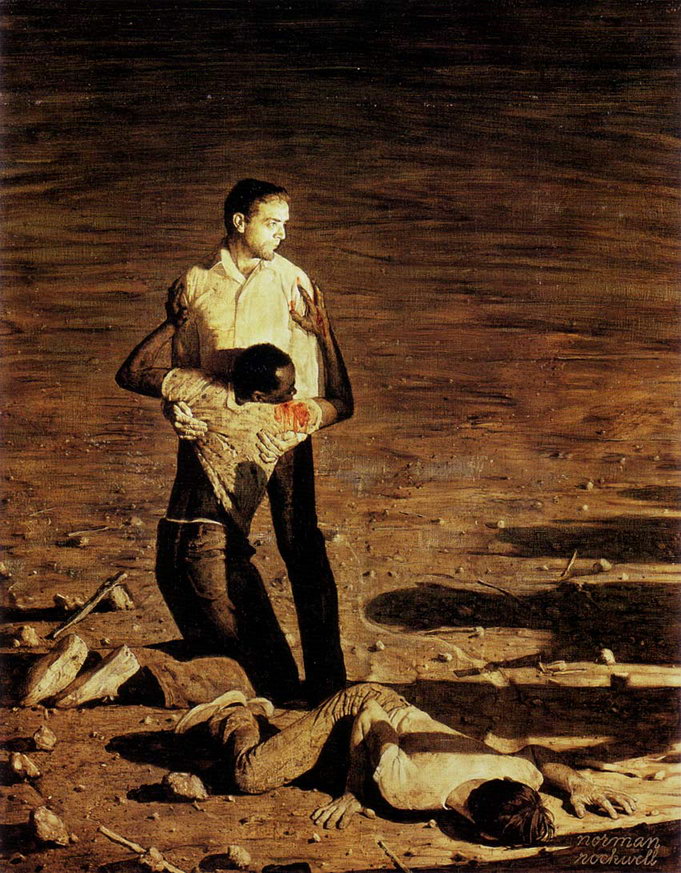

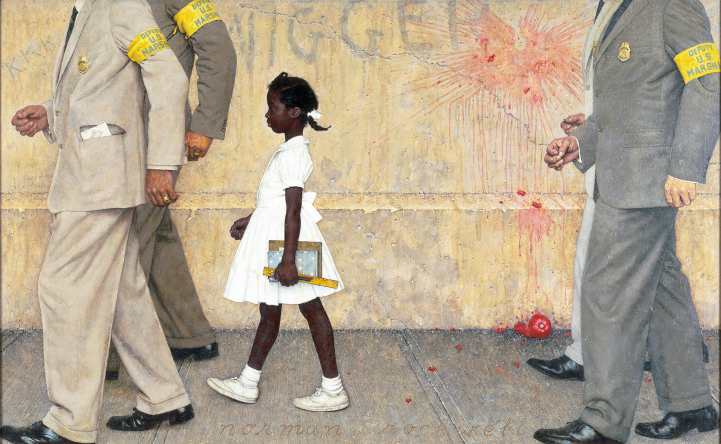

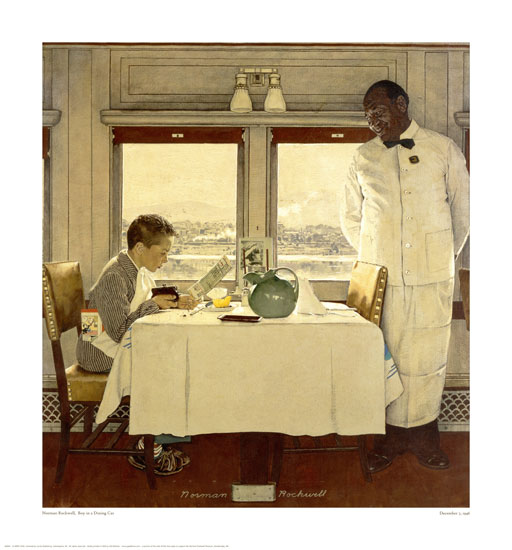

rockwell_mississippi.jpg, 179 KB

rockwell_mississippi.jpg, 179 KB

This community is focused on ideas and resources for teaching using digital historical resources.